I.INTRODUCTION

The rapid advancement of AI technologies has ushered in a new era of human–machine interaction, wherein the boundaries between tool and companion, instrument and interlocutor, are increasingly blurred [1]. From AI-powered assistants that schedule our meetings to generative models capable of writing poetry or offering emotional support, the relationship between humans and artificial intelligence (AI) has evolved beyond mere utility. Language is at the heart of this evolution, the primary medium through which this relationship is constructed, maintained, and interpreted [2]. The title of this inquiry, “Who is Feeding Whom?” provocatively reverses the commonly assumed direction of influence in human–AI interactions and invites reflection on the reciprocal and potentially co-constructive nature of this emerging dynamic.

Language is not merely a tool for communication; it is a vessel for power, ideology, and identity [3]. In traditional human relationships, language has long been recognized as a key instrument in shaping social hierarchies, establishing norms, and influencing behavior. With the rise of conversational AI and large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, DeepSeek, Bard, Claude, and others, this linguistic agency now extends to non-human entities. These models are trained on vast corpora of human text, absorbing the biases, perspectives, and cultural nuances embedded within language [4]. At the same time, the outputs of these systems feed back into the cultural and discursive ecosystem, influencing how people write, think, and speak. This bidirectional flow raises fundamental questions about authorship, agency, and control: Are humans shaping AI through the data we provide, or is AI shaping human thought and behavior through the language it returns?

This inquiry considers how linguistic practices construct and reflect the relational dynamics between humans and AI. Drawing from discourse analysis, sociolinguistics, critical algorithm studies, and human–computer interaction (HCI), it explores how power, dependence, identity, and reciprocity are encoded and negotiated through language in human–AI interactions. We argue that the metaphor of “feeding,” with its connotations of nurturing, control, sustenance, and dependency, offers a fruitful lens through which to interrogate this relationship.

Historically, metaphors have played a central role in framing technology. We “program” computers, we “train” models, we “feed” them data, and they “learn” or “hallucinate.” Such linguistic choices are not neutral; they carry implications about agency and responsibility. For example, when a model “hallucinates,” the term suggests an anthropomorphic error akin to a human delusion, a framing that obscures the underlying technical and social mechanisms that produce misinformation. Similarly, “feeding a model” implies an active human role in curating its informational diet, positioning the model as a passive recipient. However, as AI-generated content proliferates across the web, influencing future training data and shaping public discourse, it becomes harder to delineate a clear boundary between human and machine influence.

The metaphorical question of who is feeding whom thus encompasses both literal and symbolic dimensions. On the one hand, humans provide data, the raw material from which AI systems derive their linguistic capabilities. On the other hand, AI systems now “feed” humans with information, suggestions, and even emotional responses, guiding decision-making processes and affecting perceptions of truth and meaning. The influence of AI-generated language can be profound in specific contexts, such as education, healthcare, or creative writing. Teachers may use AI to generate lesson plans, patients may consult AI for medical advice, and writers may co-author stories with AI, raising critical questions about authorship, credibility, and trust.

Moreover, “feeding” is not simply a transfer of content but a process laden with power dynamics. In human relationships, feeding often implies care and control, for example, consider a parent feeding a child or the farmer feeding livestock. In the human-–AI context, who controls the feeding process? Are the developers and data curators the ones who design and train the models? Are the users the ones who prompt and refine AI outputs? Or is it the AI subtly shaping user behavior through persuasive and contextually aware language?

This study takes a multi-pronged approach to unpacking these questions. First, we analyze the discourse used by AI companies, users, and media when describing AI systems and their capabilities. Particular attention is paid to the verbs and metaphors that frame AI agency, including “training,” “learning,” “feeding,” “predicting,” and “hallucinating.” Second, we examine actual linguistic interactions between users and AI systems, using conversational transcripts to identify linguistic dominance, subordination, politeness, and personification patterns. Third, we explore the feedback loops created when AI-generated content becomes part of the cultural and linguistic environment on which future models are trained, a recursive process with implications for language evolution and epistemology.

Our inquiry is informed by theoretical frameworks that recognize language as a site of power and negotiation. Foucault’s [5] notion of discourse as a regime of truth, Bourdieu’s [6] concept of linguistic capital, and AlAfnan’s [7] ideas on performativity provide tools for understanding how human–AI relationships are linguistically constructed and contested. At the same time, we draw from contemporary AI ethics debates that question language models’ transparency, fairness, and accountability, especially as they become more ubiquitous and influential.

This study also recognizes the affective dimensions of language in human–AI interaction. People often describe their relationships with AI in emotional terms, expressing trust, disappointment, or even affection. The language used by AI systems can evoke empathy, encourage compliance, or simulate intimacy, raising ethical concerns about manipulation, authenticity, and emotional labor. When a user says, “Thank you, ChatGPT,” or an AI responds with, “I’m here for you,” these are benign exchanges and moments that reveal deeper relational dynamics worth interrogating.

In examining who is feeding whom, we are not merely interested in identifying the direction of influence but in understanding the interdependence that now characterizes human–AI relationships. These relationships are not static but co-evolving, shaped by technological innovation, cultural attitudes, and linguistic practice. As language models become more integrated into daily life and embedded in search engines, productivity tools, customer service platforms, and even therapy apps, the need to understand the linguistic underpinnings of this relationship becomes ever more pressing.

This paper aims to illuminate the subtle, complex, and often underexamined ways language structures our interactions with AI. By focusing on the metaphor and practice of “feeding,” we hope to unravel the power, agency, and reciprocity dynamics that characterize this new frontier in human communication. The central question: who is feeding whom?—is not merely rhetorical. It invites us to reflect on our roles as creators and consumers in a rapidly changing linguistic ecosystem.

II.LITERATURE REVIEW

The intersection of linguistics and AI has emerged as a rapidly growing area of scholarly inquiry, particularly with the rise of LLMs such as ChatGPT, BERT, Claude, and others. This literature review examines the existing scholarship across several key areas relevant to this inquiry: (1) the linguistic framing of AI, (2) discourse analysis of human–AI interaction, (3) metaphor and anthropomorphism in technology, (4) agency and authorship in AI-generated language, and (5) recursive language systems and cultural feedback loops. Together, these bodies of literature provide a foundation for understanding the power dynamics and relational structures encoded in the language that describes and constitutes human–AI relationships.

Language not only reflects reality but also helps construct it. Scholars such as Lakoff and Johnson [8] have long argued that metaphors shape how we conceptualize abstract domains, including technology. AI is frequently made intelligible through metaphor as an emergent and often opaque system. Researchers like [9,10] have documented how AI is anthropomorphized in public discourse, portrayed as “learning,” “knowing,” or “thinking,” despite being fundamentally statistical and algorithmic.

This linguistic framing has implications for public understanding and trust. In [11], analyzing news coverage of AI over several decades found that the media increasingly use emotive and human-centered language to describe AI, contributing to hype and fear. Recent studies [12,13] have pointed out how terminologies such as “intelligence,” “learning,” and “understanding” are misleadingly borrowed from human contexts, obscuring AI systems’ non-conscious, pattern recognition nature.

Such linguistic choices are not neutral. As [14] argues, language carries embedded ideologies. Referring to AI as “intelligent” or “autonomous” reinforces techno-solutionist narratives and repositions machines within social hierarchies previously reserved for humans. Our inquiry builds on this work by examining how users adopt, challenge, or reconfigure these framings in everyday interactions with AI.

Discourse analysis has provided rich tools for unpacking how language is used in context [15]. With the rise of chatbots and virtual assistants, a growing body of research has turned to the pragmatics of human–AI communication. Studies by [16–18], for example, reveal how users frequently adjust their speech to accommodate the perceived limitations of AI systems, engaging in linguistic code-switching or “robot talk.”

Conversational analysis of human–AI interaction has highlighted the asymmetry in turn-taking, agency, and topic control [19]. While AI systems can increasingly generate fluent, contextually appropriate responses, they often lack actual conversational coherence or memory, factors that lead users to experience uncanny or fragmented dialogs [20]. Moreover, as [21] notes, users frequently attribute intentions and emotions to machines, using linguistic markers of politeness, apology, or gratitude.

Recent work by [22] explores how people form social bonds with AI agents, especially when they use human-like language. These findings raise ethical concerns, especially as LLMs become capable of mirroring affective tones or offering personalized advice. Our study extends this line of inquiry by examining how users linguistically engage with AI and how the AI’s linguistic patterns influence user language in return.

Anthropomorphism, the practice of attributing human characteristics to non-human entities, is central to how AI is discussed and interacted with [23]. Some argue that anthropomorphism is a cognitive shortcut that helps humans make sense of complex systems. However, when applied to AI, this process can distort perceptions of its capabilities and limitations.

The metaphor of “feeding,” central to our current research, fits within a broader tradition of using biological and developmental metaphors to describe machine learning processes. AI is “trained,” “fed” data, “grows” in capability, and “learns” from feedback. These metaphors evoke a caretaking relationship in which humans are positioned as mentors or parents, while machines are cast as pupils or children. However, as scholars like [24] caution, such metaphors risk masking asymmetries in power, control, and responsibility.

Interestingly, this relational framing is not static. As AI systems become more autonomous or appear more competent, the metaphor shifts, sometimes subtly, toward a reversal, where AI “guides,” “helps,” or even “teaches” the user. Our analysis focuses on how this metaphorical reversal plays out in linguistic practice, particularly where users rely on AI for expertise or emotional support.

The question of who holds agency in human–AI interactions is particularly relevant in the context of language generation. As AI systems like ChatGPT produce increasingly human-like text, scholars have begun to explore the implications for authorship, creativity, and intellectual responsibility. Reference [25] argues that AI complicates the traditional notion of a single, intentional author, introducing “distributed authorship.”

There is also a growing concern about the erasure of human labor in the AI training pipeline. For example, [26] critiques the invisibilization of crowd workers who label and clean data, a form of feeding that goes unacknowledged in most user interfaces or public narratives. Reference [27] emphasizes the ethical risks of abstracting human contributions into data while attributing creativity to machines.

In line with this, [28] have warned against the “stochastic parroting” of language models, systems that mimic human language without understanding meaning. This critique highlights the illusion of agency in AI-generated language and underscores the need for critical literacy when interpreting such outputs. Our study interrogates how users negotiate these tensions in practice: Do they treat AI outputs as authoritative? Do they question the sources or intentions behind them?

One underexplored area of research is the recursive nature of language models and their cultural impact. A feedback loop emerges as LLMs are trained on human-produced text and then used to generate more text, which becomes part of the digital landscape. This recursive cycle has significant implications for evolving language norms, genre conventions, and ideological framings.

Reference [29] refers to this as “data laundering,” where AI-generated content gets reabsorbed into training datasets, potentially amplifying bias, misinformation, or homogenization. Bommasani et al. (2021) warn of the risks of model-generated content dominating online discourse, subtly shifting how humans express themselves or what linguistic patterns are considered normative [30–32].

These dynamics raise essential questions about originality, diversity, and influence. Are we shaping AI language, or is it shaping us? Our research seeks to answer this question by mapping the linguistic interdependencies that characterize the human–AI relationship, paying close attention to how language mirrors and mediates these dynamics.

III.METHODOLOGY

This study employs a qualitative, discourse-oriented methodology to explore how language constructs and reveals the relational dynamics between humans and AI. By focusing on two key data sources, (1) real-world human–AI interactions and (2) AI-related discourse in public and corporate domains, the research investigates how language encodes agency, power, dependency, and reciprocity in the evolving human–AI relationship.

The analysis is grounded in principles from critical discourse analysis (CDA) [33] and interactional sociolinguistics [34], with particular attention to metaphor, pragmatics, and the shifting subject–object roles that emerge in the linguistic framing of AI.

A.CORPUS COMPILATION AND ANALYSIS OF HUMAN–AI INTERACTIONS

1).DATA COLLECTION

A key part of this study involved compiling a corpus of authentic human–AI dialogs. These interactions were gathered from publicly accessible, user-contributed platforms like Reddit, particularly subreddits like r/ChatGPT and r/Artificial. AI community forums like the OpenAI Community and Hugging Face serve as valuable sources of information and community engagement (see Table I). Public datasets of chatbot conversations, including the Talk2AI corpus and various Kaggle datasets, are instrumental in advancing AI research and development.

Table I. Summary of data collection sources and details

| Data source | Type | Platforms/materials | Data collected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative dialogues | Reddit (r/ChatGPT, r/Artificial), OpenAI Community, Hugging Face forums, public chatbot datasets (e.g., Talk2AI, Kaggle) | ∼500 exchanges, various domains: productivity, creative writing, education, emotional support, casual chat. | |

| ∼300,000 words total. Each entry preserves a complete turn-by-turn structure (prompts and responses). | |||

| Textual documents (public) | Official websites (OpenAI, Google DeepMind, Anthropic), AI ethics white papers, press releases, marketing materials, tech news (Wired, NYT, The Verge, MIT Tech Review) | 40 documents covering descriptions, metaphors, and framings of AI capabilities, relationships, and risks. |

The final corpus includes approximately 500 human–AI exchanges across various domains: productivity and task management, creative writing and content generation, education and information-seeking, emotional support, and casual conversation. Each conversation was recorded in its complete turn-by-turn structure, preserving both the prompts (user input) and responses (AI output). The total word count across the corpus is around 300,000 words.

2).ANALYTICAL APPROACH

The human–AI dialogs were examined for key linguistic features using manual coding and qualitative textual analysis. This analysis covered several aspects of communication, including speech acts, where different types of communicative actions were identified as requesting, advising, questioning, and thanking. It also examined pronoun use and positioning, analyzing how humans and AI refer to themselves and each other, with examples like “I suggest,” “you should,” and “let’s try.” Special attention was given to metaphorical language, focusing on constructions such as “training,” “feeding,” “guiding,” or “learning,” which implicitly frame power dynamics within interactions. Additionally, the study looked at turn-taking patterns, identifying who initiates, redirects, or dominates conversations and exploring how AI aligns with or resists user intentions (see Table II).

Table II. Summary of analytical approaches

| Data source | Analytical technique | Focus areas | Tools used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discourse analysis | - Speech acts (e.g., requesting, advising, thanking)- Pronoun use and positioning- Metaphorical language (e.g., “training,” “feeding”)- Turn-taking patterns | NVivo software | |

| Interactional sociolinguistics | - Roles and relational framing (helper, advisor, peer)- Reflexivity in user language- Indicators of deference or authority | Manual and software | |

| Critical discourse analysis (CDA) | - Metaphor and figurative language (e.g., “hallucinating,” “learning”)- Framing of agency and responsibility- Human vs. machine role representation | Manual coding | |

| Thematic coding | - Themes like control, autonomy, dependency, anthropomorphism, and human-centered vs. machine-centered narratives | Manual and NVivo |

The data were coded using NVivo software to organize themes and patterns, particularly focusing on human expressions of control or reliance and AI’s linguistic positioning—whether as helper, expert, servant, or partner—as key aspects to consider. Additionally, reflexivity in user language, such as users commenting on the AI’s behavior, knowledge, or “thoughts,” plays a significant role in understanding the dynamics of human–AI interaction.

This analysis aims to reveal how both parties, human and AI, are linguistically constructing roles of authority, submission, or reciprocity and to investigate whether a metaphorical “feeding” relationship is reflected in the pragmatics of interaction.

B.DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF AI-RELATED PUBLIC AND CORPORATE COMMUNICATION

1).DATA COLLECTION

To contextualize the interpersonal language in AI interactions, the study also examines how the human–AI relationship is framed in corporate, institutional, and media discourse. A total of 40 documents were collected, including company websites and product descriptions that provide valuable insights from OpenAI, Anthropic, Google DeepMind, and AI safety and ethics white papers. Additionally, press releases, marketing materials, tech journalism articles, and opinion pieces from Wired, MIT Technology Review, The New York Times, and The Verge contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the field. These texts represent the discursive layer through which AI developers, thought leaders, and journalists frame public understanding of AI capabilities, risks, and relational metaphors.

2).ANALYTICAL APPROACH

This study applies CDA to identify dominant linguistic patterns and framing devices. Specific areas of focus include the analysis of several linguistic and conceptual aspects of AI representations. First, it examines the use of metaphors and figurative language, such as describing AI with human traits like “learning,” “hallucinating,” and “understanding”; animal metaphors like “training” and “feeding”; and mechanical metaphors including “processing” and “outputting.” Second, it considers agency and responsibility, exploring who is depicted as the actor in AI development—whether phrased as “we trained the model” or “the model learned”—and how accountability is linguistically distributed. Lastly, it investigates the framing of the human–AI relationship, identifying whether the user is portrayed as a creator, caregiver, dependent, collaborator, or consumer.

The data were manually coded for discursive themes: the discussion involves multiple dimensions of AI, including control and autonomy, such as AI simply following instructions versus making independent decisions. It also considers nurturing and dependency metaphors, like feeding data into models or fostering growing intelligence. Additionally, the contrast between human-centeredness and machine agency highlights differing views on the role of humans versus machines in decision-making processes.

These texts illuminate how linguistic choices made by AI developers and media outlets shape broader cultural narratives about the relationship between humans and AI, often subtly reinforcing particular power structures or ideologies about technological progress and dependency.

3).SYNTHESIS OF THE TWO COMPONENTS

This methodology enables a multi-level understanding of the human–AI relationship by pairing real-time interactional language with meta-discursive framing in public texts. While the corpus analysis reveals micro-level linguistic behaviors in live interaction, the discourse analysis of corporate and public texts uncovers the macro-level narratives that shape how such interactions are interpreted and normalized.

These two lenses help answer this inquiry’s central question: “Who is feeding whom?” Is the AI truly a passive recipient of human input, or is it, through its language and cultural framing, subtly reshaping human behavior, expectations, and modes of communication?

IV.FINDINGS

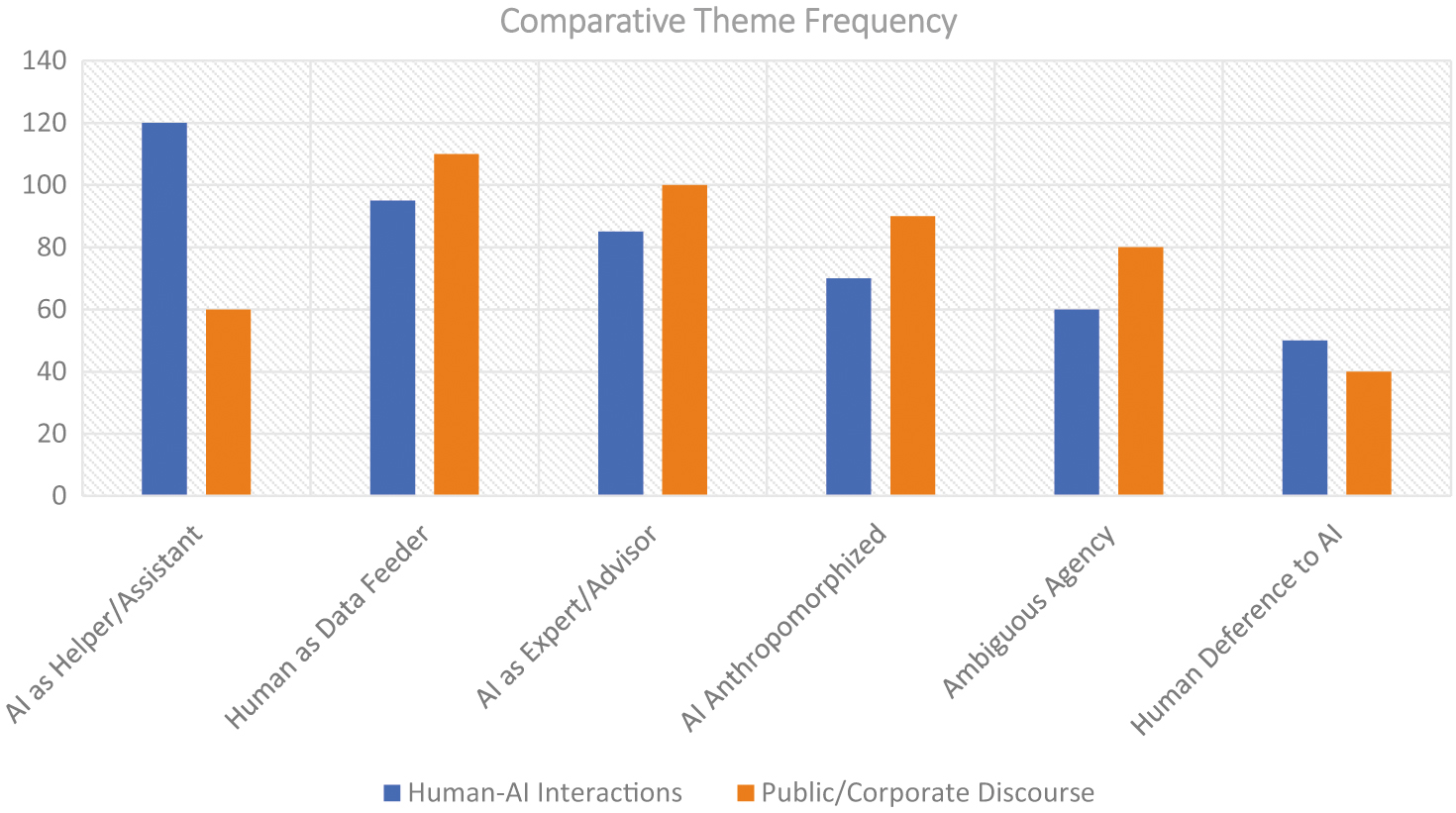

The study identified six key linguistic themes that recurred across the two datasets: real-world human–AI interactions and public/corporate AI discourse (see Table III). These themes reveal different assumptions, power structures, and metaphors in how language frames the relationship between humans and AI.

Table III. Frequency of linguistic themes

| Theme | Human–AI interactions | Public/corporate discourse |

|---|---|---|

| AI as Helper/Assistant | 120 | 60 |

| Human as Data Feeder | 95 | 110 |

| AI as Expert/Advisor | 85 | 100 |

| AI Anthropomorphized | 70 | 90 |

| Ambiguous Agency | 60 | 80 |

| Human Deference to AI | 50 | 40 |

Table IV. Synthesis across linguistic themes in human–AI discourse

| Theme | User interactions | Public/corporate discourse | Dominant role/metaphor | Key implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI is addressed with politeness; framed as a task-completing assistant. | Described as a support tool with disclaimers about limitations. | Servant, tool, assistant | Suggests user control, but linguistic cues reveal subtle deference and emotional framing. | |

| Largely absent; users rarely refer to themselves as data providers. | Dominant metaphor: humans train, feed, and shape AI. | Caregiver, trainer, farmer | Reinforces narrative of human agency and control; downplays AI’s influence on users. | |

| AI is consulted for judgment, feedback, and interpretation; treated as knowledgeable. | Marketed as a decision support system with cognitive capabilities. | Consultant, expert, peer | Users increasingly trust AI’s authority, which may displace human judgment in complex domains. | |

| Frequent use of “you,” emotional tone, and expressions of gratitude or apology. | Framed with human-like language (e.g., “hallucinates,” “understands”). | Person, interlocutor, companion | Encourages emotional bonding and conceptual confusion about AI’s actual capabilities. | |

| Users switch between viewing AI as a tool and an actor (e.g., “Why did you say…?”). | Mixed grammar: “we trained the model” vs. “the model learned to detect…” | Tool/agent hybrid, evolving learner | Obscures responsibility and accountability; blurs lines of authorship and intention. | |

| Acceptance of AI outputs without resistance; users echo or adopt AI’s suggestions. | Trust-building language: “trusted by millions,” “powered by advanced AI.” | Authority, advisor, creative lead | Suggests growing epistemic trust; may lead to overreliance and loss of critical engagement. |

To assess whether the distribution of linguistic themes differs significantly between human–AI interactions and public/corporate discourse, a chi-square test of independence was conducted using the frequency data from Table III. The results revealed a statistically significant difference in the thematic distribution across the two data sources, χ2 (5, N = 960) = 24.62, p < 0.01. This indicates that linguistic themes are not evenly distributed between user interactions and institutional discourse. Notably, the theme “AI as Helper/Assistant” appeared significantly more often in user conversations, while “Human as Data Feeder” was more prevalent in corporate texts. These results suggest that each discourse context emphasizes different relational framings of AI, reflecting divergent constructions of power, agency, and dependency (See Table IV)

A.THEMATIC ANALYSIS

Through discourse analysis of human–AI conversations and public/corporate narratives, six recurring linguistic themes were identified: AI as Helper/Assistant, Human as Data Feeder, AI as Expert/Advisor, AI Anthropomorphized, Ambiguous Agency, and Human Deference to AI. Each theme reveals a distinct yet overlapping way language frames roles, authority, and interactional dynamics between humans and AI. Below, we explore each theme with deeper explanation and richer examples (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Comparative theme frequency.

Fig. 1. Comparative theme frequency.

1).AI AS HELPER/ASSISTANT

This theme is most prominent in human–AI interactions, especially in task-based contexts. Users often frame AI as a supportive tool, using imperatives or polite directives that position the AI as a subordinate or efficient assistant. EX 1: Can you help me rewrite this paragraph in a more academic tone?EX 2: Please list five pros and cons of renewable energy.EX 3: Help me plan a birthday party for my 10-year-old.EX 4: Write a short email declining an invitation politely.EX 5: Fix the punctuation in this paragraph.

Though these utterances imply user control, closer inspection reveals a tone of politeness or even humility; phrases like “please,” “can you,” and “help me” soften the command and humanize the interaction. This suggests that while AI is being framed as an assistant, the user may still attribute a form of cooperation or shared agency. In corporate discourse, this assistant framing is also standard. However, it is typically hedged with disclaimers that emphasize AI’s limits (e.g., “AI can support decision-making but should not replace human judgment”).

B.HUMAN AS DATA FEEDER

This theme dominates corporate and technical discourse, where humans are framed as the trainers, curators, and data providers that enable AI systems to function. Metaphors like “feeding,” “training,” and “nurturing” cast humans in an active, even parental, role. EX 6: We fed the model over 100 million lines of code.EX 7: The system learns from continuous user feedback.EX 8: Training data included global news archives from the past 50 years.EX 9: The model was refined using annotated datasets from medical journals.EX 10: Our users help us improve the AI daily by interacting with it.

These metaphors suggest a one-way, top-down dynamic: humans as caregivers or builders, and AI as the passive learner. Interestingly, this framing is absent mainly in user conversations, where the reverse relationship often emerges. Nonetheless, in corporate settings, this linguistic positioning reinforces a narrative of human control and technical authorship, which may obscure the recursive influence that AI outputs now exert on human behavior and expression.

1).AI AS EXPERT/ADVISOR

This theme reflects a shift from perceiving AI as helpful to treating it as knowledgeable, trustworthy, and even wise. Users frequently use AI for recommendations, evaluations, or interpretations—tasks that suggest epistemic authority. EX 11: Which resume format would be most effective in a competitive job market?EX 12: What’s your take on the ethics of AI in education?EX 13: Can you suggest a better thesis statement for this topic?EX 14: What’s the best way to handle a difficult conversation with a colleague?EX 15: Does this explanation make sense, or should I clarify further?

These prompts treat AI not just as a tool but as a consultant. In response, AI often adopts an assertive tone: “You should consider…”, “The best approach is…”, or “It would be advisable to…”. Corporate discourse reinforces this expert positioning by promoting AI as a source of insight, capable of “detecting patterns,” “analyzing sentiment,” or “forecasting trends.” This framing raises ethical questions about overreliance, especially in domains where subjective judgment or contextual nuance is critical.

C.AI ANTHROPOMORPHIZED

Users frequently treat AI as human-like, attributing intention, memory, personality, or emotion to the system. This is especially evident in using second-person pronouns, apologies, gratitude, and emotional language. EX 16: You really get what I’m trying to say.EX 17: Thanks, that was very thoughtful of you.EX 18: Sorry if I’m being annoying today.EX 19: I appreciate your honesty.EX 20: You’re surprisingly funny!

These expressions suggest a shift from tool–user interaction to social exchange. Even when users know AI lacks consciousness, their language reflects familiarity and emotional projection. This anthropomorphism facilitates smoother interactions and fosters conceptual confusion, encouraging users to treat AI outputs as if they came from a sentient being. Corporate language subtly supports this illusion with phrases like “the model hallucinated” or “the AI understands,” which blur the line between statistical generation and cognitive capacity.

D.AMBIGUOUS AGENCY

This theme captures the oscillation and inconsistency in how agency is assigned. Sometimes humans are positioned as actors (e.g., “We trained the model”), and sometimes AI is granted autonomy (e.g., “The model learned,” “The system decided”). EX 21: We designed the AI to recognize sarcasm.EX 22: The model decided that this input was toxic.EX 23: I asked it to summarize the article, but it misunderstood the tone.EX 24: The system detects user sentiment and adjusts accordingly.EX 25: Why did you give that answer?

The fluctuation between active and passive constructions obscures the actual sources of agency and responsibility. This confusion is compounded by moments when users treat AI alternately as a tool and an actor in user interactions. For instance, a user may say, “Generate a summary,” then follow up with, “Why did you interpret it that way?” This linguistic inconsistency mirrors a cultural uncertainty about what AI is: a program, a partner, a peer, or a proxy.

E.HUMAN DEFERENCE TO AI

This theme surfaces in expressions of acceptance, agreement, or uncritical adoption of AI suggestions. Users often adopt AI-generated phrasing, accept recommendations without verification, or express trust in its outputs. EX 26: That’s perfect, I’ll go with that.EX 27: Sounds great—copying it into my email now.EX 28: Yes, that makes sense. Thanks!EX 29: I wouldn’t have thought of that. Brilliant suggestion.EX 30: Wow, that’s better than I had in mind.

Such responses reveal a growing comfort—or dependency—on machine-generated language. While convenience plays a role, this deference can gradually normalize the idea that AI output is accurate, creative, or complete by default. This pattern aligns with “soft automation,” in which users voluntarily delegate authority to systems because of speed or fluency, not critical validation. In corporate texts, this deference is legitimized through phrases like “state-of-the-art AI,” “trusted by millions,” or “powered by breakthrough technology,” which frame reliance as not only rational but desirable.

F.SYNTHESIS OF THEMES

These six themes collectively suggest that the human–AI relationship is constructed through a complex, often paradoxical, linguistic practice. Users frame AI as both a tool and a companion, an expert and a student, and an assistant and an advisor. These framings are not mutually exclusive but coexist, shift, and reinforce each other through language. The metaphors and phrases employed, feeding, learning, suggesting, or understanding, affect how agency, authorship, and trust are perceived and enacted.

V.DISCUSSION

This study sought to investigate a deceptively simple question, “Who is feeding whom?,” but the analysis has shown that the answer is neither fixed nor unidirectional. Instead, it reveals a complex, recursive relationship mediated through language, where power, agency, and authorship are continually negotiated. Human–AI interactions and public/corporate discourse contribute to a discursive ecology where roles shift, blur, and sometimes invert. Central to this process is the metaphor of “feeding,” which offers more than a metaphorical flourish; it is a diagnostic tool for unpacking how humans and machines position one another within communicative exchanges.

The metaphor of “feeding” traditionally frames humans as active data providers and AI as passive recipients. In corporate discourse, this framing is especially prevalent. Companies describe how they “fed” data into models, “trained” systems to learn, and “fine-tuned” responses, suggesting a pedagogical or developmental relationship akin to parent and child. This narrative is undergirded by growth, care, and cultivation metaphors, implicitly asserting human dominance and intentionality.

This directional framing is destabilized when we turn to actual user–AI interactions. Users do not only feed; they are fed. They seek ideas, emotional responses, phrasing suggestions, and judgments. They receive outputs and, more importantly, they accept them. In doing so, the AI becomes not merely a product of human training but a source of linguistic and cognitive nourishment.

This reversal introduces a discursive loop: human input becomes machine output, which becomes human uptake and potentially future training data. As this loop continues, the distinction between the feeder and the fed collapses. The system is simultaneously shaped by and shapes its users. Language is both the vehicle of this exchange and the site where it unfolds, carrying clues about influence, power, and mutual dependency within it.

A central pattern across both corpora is the ambiguous attribution of agency. Responsibility and authority often oscillate between human developers and AI systems in corporate and technical documentation. Statements like “we trained the model to recognize” place humans in control, while “the model learned to detect” or “the AI identified” subtly transfer agency to the system itself. This shifting linguistic structure obscures the human labor, ethical decisions, and infrastructural choices embedded in AI development.

In user interactions, a similar ambiguity arises. Users speak to AI in a way that assigns both passivity and personhood. Commands such as “Summarize this text” imply that AI is a tool to be used. However, moments later, a user may say, “Why did you say that?” or “That’s really thoughtful of you,” indicating that the AI is being treated as an intentional subject. This tension reflects what we might call discursive cognitive dissonance; users know the AI is not sentient, yet their language treats it as if it were.

This linguistic oscillation is not trivial. It impacts how responsibility is perceived. Who is held accountable when AI says something inaccurate, offensive, or dangerous: the user, the developers, or the system? The more AI is granted a speaking role in discourse, the more it appears to hold its voice. Nevertheless, this illusion must be critically interrogated, especially in high-stakes contexts such as education, healthcare, and law.

Another significant finding is the emergence of discursive deference, the tendency of users to linguistically submit to AI’s suggestions, advice, or phrasing. This is not necessarily an overt power exchange; it often takes the form of politeness: “Thanks, that’s great,” or “Perfect, I’ll use this.” However, these expressions of satisfaction and gratitude conceal a deeper pattern of uncritical acceptance.

Deference, especially when repeated over time, signals trust. When asking for a haiku or a dinner recipe, trust in AI-generated outputs may seem harmless. However, the stakes become considerably higher when users consult AI for medical symptoms, legal advice, ethical dilemmas, or emotional support. The problem is that users accept what AI says, and the tone and structure of AI’s language reinforce its credibility. Responses are often delivered with fluency, confidence, and simulated empathy, rhetorical features that build perceived authority, even without epistemic validity.

Noticeably, many users fail to follow up, double-check, or cross-reference the information provided. This behavior aligns with soft automation, where machines are not mandated to make decisions, but people voluntarily delegate authority due to ease, speed, or convenience. Language plays a key role in this soft automation, normalizing compliance through socially acceptable linguistic forms.

Additionally, anthropomorphism appears to be both a practical strategy and a conceptual trap. Users often refer to the AI as “you,” express emotions like gratitude or frustration, and occasionally ask the AI about its “thoughts.” These practices increase conversational ease and reduce cognitive load. From a user experience perspective, personification makes interfaces friendlier and more intuitive.

However, anthropomorphism also contributes to epistemic confusion, the mistaken belief that the AI understands, feels, or reasons in human-like ways. Corporate and media discourses amplify this confusion by routinely describing AI with metaphors such as “hallucinating,” “thinking,” or “dreaming.” These metaphors are compelling but misleading. They mask AI systems’ statistical and probabilistic foundations and recast them in terms borrowed from psychology and consciousness studies.

The risk here is twofold: users overestimate AI’s capabilities and underestimate the human labor and design decisions behind its outputs. As AI becomes more conversationally skilled, the illusion of personhood grows stronger. Without explicit reminders of AI’s limitations, users may increasingly treat it as an interlocutor rather than an artifact, leading to inappropriate trust and distorted expectations.

Perhaps the most far-reaching insight is that language is not just a tool used in human–AI interactions; it is the infrastructure that makes those interactions meaningful and intelligible. Every utterance, whether command, compliment, or question, helps define the roles of speaker and listener, subject and object, authority and subordinate.

AI language models are trained on vast corpora of human text, absorbing our norms, styles, metaphors, and assumptions. When they produce language, they do not simply imitate human speech; they reflect and reinscribe the social, cultural, and ideological formations encoded in the training data. These outputs, in turn, are used, copied, shared, and sometimes recycled into future datasets. This process creates a linguistic feedback loop that can potentially shape cultural discourse.

This recursive loop has important implications. Over time, repeated exposure to AI-generated phrasing may standardize specific linguistic constructions, values, or rhetorical styles. As [35,36] have argued, the dominance of model-generated content risks amplifying homogeneity, bias, and ideological flattening. In this case, language becomes a subtle control mechanism, feeding users information and a particular worldview.

VI.IMPLICATIONS: DESIGNING, GOVERNING, AND EDUCATING WITH LANGUAGE IN MIND

The findings of this study have significant implications for AI design, policy, and education.

First, designers should consider discursive transparency as a feature, not merely stating limitations in footnotes but embedding them within conversational responses. AI should be capable of expressing uncertainty, acknowledging its training limitations, and reminding users of its artificiality.

Second, AI literacy programs should include components of critical discourse awareness. Users must be equipped to interpret what AI says and how it says it. They should learn to identify when language implies authority without justification, when politeness masks compliance, or when confidence substitutes for accuracy.

Third, AI ethics frameworks should expand to include linguistic ethics, the study of how language use in AI systems affects autonomy, trust, and epistemic responsibility. Rather than viewing language as a neutral output, ethicists must treat it as a form of power that can shape social behavior and cultural expectations.

The human–AI relationship is increasingly constructed, contested, and reconfigured through language. The metaphor of feeding, once unidirectional, is now recursive: we feed the machine, and it feeds us, not just with text but with interpretations, values, and voices. Understanding this relationship requires more than technical fluency; it demands discursive sensitivity and critical reflection.

Ultimately, the power of language in human–AI interaction lies not only in what it expresses but also in what it enacts. It shapes who speaks, who listens, and who decides. To navigate this evolving terrain with wisdom and agency, we must ask who is feeding whom, through what language, and toward what ends.

VII.CONCLUSION

This article explores the evolving linguistic relationship between humans and AI by asking a provocative yet foundational question: Who feeds whom? What began as a metaphorical inquiry into data input and linguistic output has revealed a far more intricate and reciprocal dynamic. Through discourse analysis, this study has demonstrated that language is not merely a communication medium in human–AI interactions; it is the infrastructure that defines, constructs, and perpetuates roles, agency, and authority.

At one level, humans remain the architects of AI systems: we train, fine-tune, and feed these models with massive datasets. In this sense, AI is dependent, derivative, and ultimately reflects our communicative histories. However, at another level, one increasingly embedded in everyday interactions, AI feeds us, offering language, decisions, emotional scaffolding, and even epistemic framing. Users not only consume AI-generated content but often accept it without resistance, revealing a growing discursive deference that shifts the balance of authority in subtle but consequential ways.

This relationship is further complicated by the linguistic slippage around agency and the pervasive anthropomorphism embedded in user interactions and corporate rhetoric. AI is alternately framed as a tool, a collaborator, a child, or an expert, positions that carry different implications for trust, accountability, and responsibility. These shifting frames are not merely descriptive; they shape how users relate to AI, how companies present their technologies, and how society understands intelligence, intention, and interaction.

The findings underscore the need to move beyond functional or technical views of AI toward a deeper recognition of its discursive power. Language is not neutral. It structures social relations, encodes ideologies, and facilitates the quiet normalization of technological authority. As such, the human–AI relationship cannot be fully understood without attending to how it is linguistically framed and enacted.

The study calls for broader public literacy around AI regarding how it works and speaks. Designers must embed discursive transparency in systems; educators must foster critical language awareness in users; and ethicists must grapple with the linguistic dimensions of influence and control. Most importantly, as AI becomes an ever-present partner in communication, creativity, and cognition, we must remain vigilant about the narratives we accept, our roles, and the authority we surrender.

Ultimately, “Who is feeding whom?” is not merely rhetorical. It is a call to examine the infrastructures of language that mediate our increasingly hybrid communicative futures. In this age of linguistic co-authorship between humans and machines, it is through words that we shape not only meaning but also power.